Exactly one year.

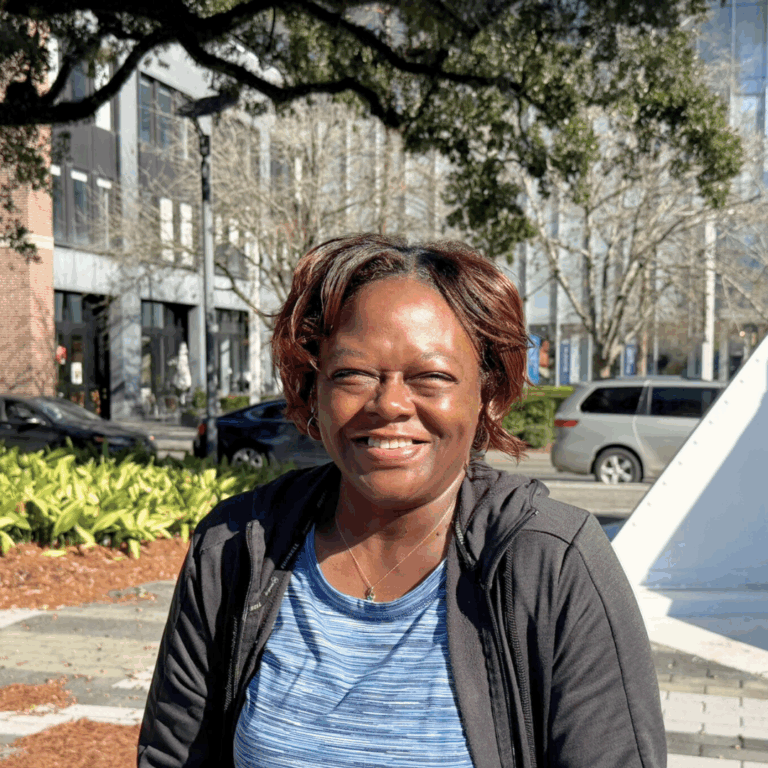

That’s how long Lisa had been home when she sat down to be interviewed on Dec. 20, 2025. She pauses and then laughs when trying to find an adequate word to describe what it feels like to be home.

“Colorful,” she finally said, shaking her head. And by colorful, she means all the colors on the emotional wheel of being human. “Good, bad, joyful, overwhelming, emotional, not so emotional, hopeful,” said Lisa, who was 31 years old when she went to prison for second-degree murder. “The full human experience, all packed into twelve months of learning how to live again.”

In 2024, with new evidence, she was able to have her second-degree murder conviction vacated and was resentenced to manslaughter, going from life without parole to a term of 23 years and immediate release.

Coming home after nearly twenty years in prison – her release date was just 10 days shy of the anniversary of her incarceration – meant stepping back into a world that had transformed. “I tell people it was the dinosaur era when I went in, and the Jetsons era when I came out,” she said. “Everything is technical now.”

Phones, apps, job applications – every step required a new skill for Lisa. But she didn’t have to navigate the changing technological landscape alone. “I had a better experience trying to figure it all out because Parole Project helped me through it all,” she said. “JP helped me do a resume and all of the tech classes were so helpful, but it’s still overwhelming at times because I’m still learning.”

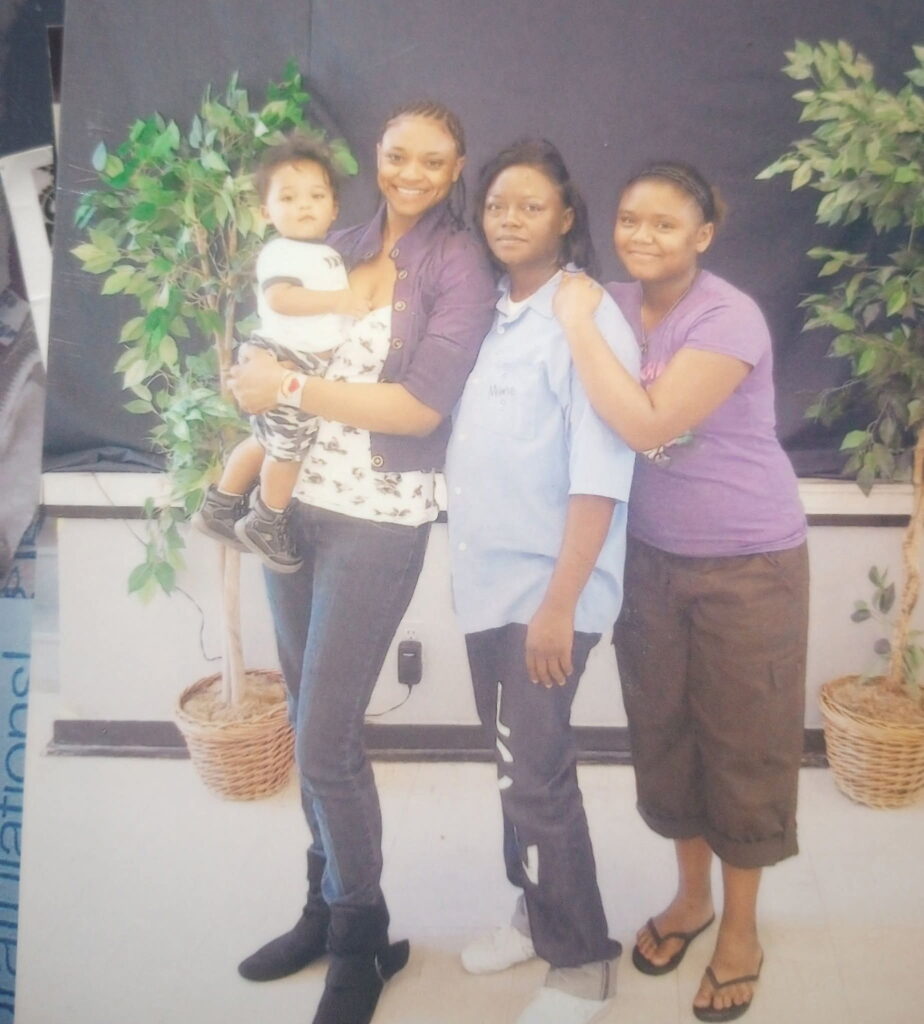

The most emotional part of coming home wasn’t technology, though. It was her daughters – Jerrica, Alyssa and Rachael – who she had spent two decades loving from a distance. “To be incarcerated and away from my girls was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. My youngest was six years old when I went in,” she said. “What was tearing me apart by being away from them, was also the thing that gave me strength not to give up. Being able to reconcile with my kids and coming out on the other side of the gate, it was overwhelming in a good way.”

But freedom comes with its own emotional weight. “When you’re incarcerated, your emotions have to be suppressed,” she said. “You can’t worry about people on the outside. You have to semi-let go just to survive.”

For Lisa, returning home meant relearning how to process her feelings and respond to real-life emotions she hadn’t allowed herself to express in prison. “If you don’t have a support group, it’s hard. I like to talk things out,” she said. “Thank God I have people I can talk to.”

Today her support system is wide and steady: friends who returned home from prison before her and Christi Cheramie, a reentry manager from Parole Project, her case manager and friend and someone she knows she can call anytime.

Since coming home, she’s built her life piece by piece. She secured a housekeeping job at a downtown hotel in February, her sister gave her a car that same month and in July, she moved into her own apartment.

Lisa is also a junior studying at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. She’s not sure where that path will lead, maybe mission work or maybe being an interpreter with another language, specifically in Spanish or French. She once went to school for hair but didn’t finish. “I really don’t know what I want to do,” she said with a smile. “But I’m open.”

Living in Parole Project’s transitional house gave her the space she needed to breathe.

“It felt like home,” she said. “It was something nice and comfortable and there weren’t a whole lot of people around. I was grateful for that space and time to reflect.” She learned to slow down, to stop comparing herself to others, to give herself grace.

“I’m impulsive by nature. I had to pump the brakes and remind myself I don’t have to be further along. I’m learning.”

Lisa has always been driven and tenacious. She was born at seven months in Lake Charles, the oldest of seven children, and her mom was 15 years old when Lisa was born.

“I had to fight to live because I was born so early so I guess I had this quiet reserve about me,” she said. “I was shy and quiet and growing up with that many brothers and sisters, I never wanted a big family, I always thought the more kids you have, the less you can distribute that attention. Kudos to people who have big families, but that just wasn’t for me.”

She grew up in a neighborhood near downtown where everyone knew everyone. Her father has passed, and she still grieves him. As a child, she loved to write poetry, dance and play teacher. “I loved teaching,” she said. “I loved school and was always naturally curious.”

Her daughters and 10 grandchildren remain her anchor. What brings her the most joy now is seeing her daughters get along. “You’re all you have,” she said she tells them. “Be there for each other.” She did what she could from prison, but now she can guide them in the physical world again.

The song “Only You” by David Allen reminds her of them. Music is one of her joys – Christian and gospel most of all, but also reggae, pop, and country. “It’s always the message,” said Lisa. “I want to hear something inspiring.”

Because she lives in Baton Rouge and her daughters live in Lake Charles, they Facetime often. Her youngest bought her a Winnie the Pooh keychain so she’d always have a reminder of them close by. Her oldest daughter picks her up and brings her home for visits. They cook together – a roast, a hen, even gumbo.

“She cooks really well,” Lisa said proudly of her oldest daughter, Jerrica. “She bakes from scratch.”

Lisa loves jigsaw puzzles, too, which help her get out of her own head. “I’m an overthinker,” she said. She wants to travel now to Detroit, the Caribbean, Europe. She’s never been on a plane, but she plans to change that.

Her definition of success is simple, hard-earned and worth repeating.

“It’s not about how many times you fall. It’s about how many times you decide to rise,” she said. “When the problems seem overwhelming, keep pressing.”